What is Father’s Day when your father is dead?

I wrote this piece for Father’s Day 2018, just a couple of short months after my dad’s passing. I’m republishing it here because… well, it’s relevant.

A young Oscar and a *VERY* young Laurel visiting a beach in California, sometime in mid-1990

A little over three months ago, I sat at my father’s bedside, holding his hand as my brother and I made the unspeakably painful decision to place him on “comfort care” — a far-too-casual euphemism for making him comfortable as he passed away.

The room was packed full of medical equipment and family. Myself, my brother, our uncle, and my father’s long-time companion. Two of us on one side, crammed next to heart rate monitors and IV bags, two on the other bumping against a reclining chair the nurses had brought in so at least one of us could sleep. Seventeen hours had passed since that decision, and there was nothing to do but wait. Over three days, none of us had showered more than once, we had dined on nothing but hospital cafeteria food and drank next to nothing except waiting-room coffee. I had caught five- or ten-minute naps in that recliner, interrupted by the beeping of a monitor giving an abnormal reading or, in one particularly aggravating instance, an intern attempting to wake my father to give him a neurological exam.

When the time came for him to pass, we were there. At his side. I kissed his forehead and had a moment with him to say goodbye. I cried harder than I had ever cried, though the shock-insulated feelings I had paled in comparison to the grief I would feel in the days and weeks after. The tube came out, his breathing slowed, then stopped. I held his hand as his heart stopped beating and the man who for twenty-nine years had been a fixed point in my life — a constant star in the sky — disappeared with a breath.

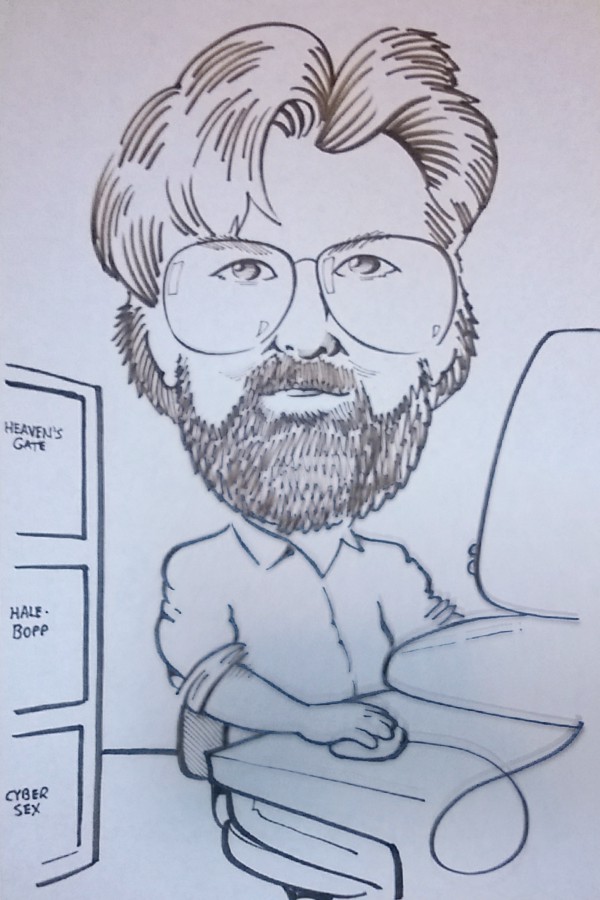

Dad really liked this caricature, which was drawn at Riverfest in the late-1990s.

Someone said that grief comes in waves. The first ones crash relentlessly, taller than a skyscraper, defying attempts to ignore them or pack them away. Then, they’re just as tall, but a little less frequent, and then they slowly become smaller and smaller until only small ripples are left. I don’t know if that’s true, but it seems as good an explanation for how some days I can be joking with family about how Dad used to always ask for his eggs overeasy because, he’d say, “that’s how I like my women” (he was #problematic sometimes) and be fine, but other times — like the night that I am writing this essay — the thought of his absence is like a maw opening in my chest.

While my father was in the ICU, before we knew how bad it was, when there was still hope and he was still awake and responding and laughing at our nervous attempts to crack jokes, I stepped out into the hospital’s courtyard to take a phone call related to a job I was pursuing. The reasoning was simple. Dad had taken an interest in my work from the moment he saw the joy I derived from it, so he’d never want to be the excuse for me passing up an opportunity to do more good work on a wider scale. When I went up to his room, I told him — “I think I got it!”

He gave me a thumbs up, and smiled as much as he could given the tube helping him breathe.

I wouldn’t have imagined a decade ago how important it would be to me that some of my last words to my father spoke to my successes. When I was ten years old, coming to grips with my identity and my place in the world, I came out to my mother — who promptly pushed me back in the closet. A dozen years later, when I told my father, he reacted first with sadness — not because he hated me or no longer loved me or was disappointed, but because he wanted to know what he did to make me keep this from him for so long. “Unconditional love means just that — love, unconditionally” he said. I often wonder what might have happened had I told him instead. Would he have moved me out of Arkansas and to a place where I could have gotten appropriate medical care? Maybe. Probably. It might have saved me a dozen years of repression, a stint in Bible College, and a marriage filled with profound regret.

In just a couple of weeks, it’s Father’s Day. I have a more complete picture of who my father was in his death than I did in his life. He was an inherently good man, though with some incredibly problematic moments. He was a man I had practically no relationship with to speak of for over a decade, but who became an incredibly important part of my life over the past few years. He was a person whose help was instrumental in making a life-changing cross-country move happen. I would not be who I am today without my father’s influence in my life.

When he was alive, I knew what Father’s Day was. When I was a child it was a goofy tie picked out by my mother and a hug. As an adolescent it was giving a card with just a signature inside to the man in front of me while I searched desperately for a father figure elsewhere. As an adult it was a meaningful handwritten note and a bottle of decent whisky and a phone call. What is it now?

I don’t know.